According to science communicator Craig Cormick (2019), the elements of effective science communication are so simple it uses fewer characters than a tweet:

- Know your audience

- Tell a good story

- Know why you are telling that story

Of course, explaining effective science communication takes more words. In fact, Cormick wrote a whole book on it, The Science of Communicating Science, where the above advice appears. But one of the two keywords is “story” – the most effective form of communication.

Evolution wired us for storytelling. Long before the abstract nature of cave drawings and writing appeared, there was only the spoken word. Stories around the campfire conveyed information for survival – when and what to hunt, what to eat and what to avoid, and how to stay safe. Children learned beliefs and values from stories about the land and the sky.

One story about a small cluster of stars called the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, could be as old as 100,000 years at the dawn of the development of the spoken word.

Stories prompt emotions, making memories ‘sticky’ – not easily forgotten. We remember childhood fairytales not because we rote learned them. Still, because they stay in our brain’s emotional memory centres, the amygdala and hippocampus are both implicated and involve the Theory of mind: understanding what others are doing. That is important: Understanding what others are doing. Storytelling is about people. We feel empathy for people and animals, driven by what other living things are doing.

Neuroscience supplies some insight into the assertion that stories affect the brain in ways other forms of communication do not. Californian neuroscientist Paul Zak found that stories prompting empathy made people more likely to donate money. Watch this short YouTube video:

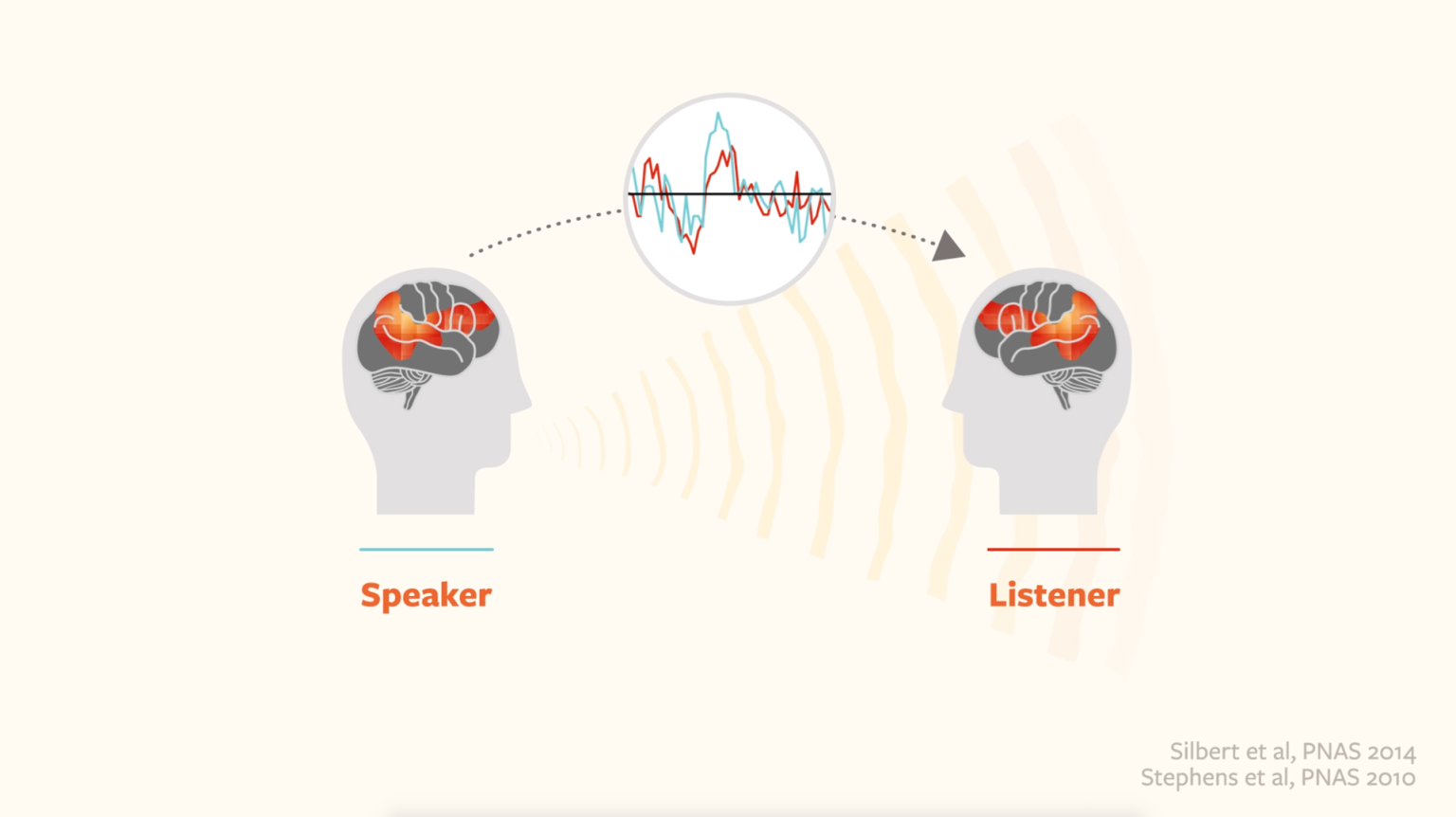

Princeton University neuroscientist Uri Hasson discovered the basis for TED talk curator Chris Anderson’s assertion that there is no magic formula for TED talks: Our brains like to ‘couple’, and the best TED talks occur when the presenter successfully transfers their idea into the brains of the audience. In fact, if successful talks could be tracked in an MRI, Hasson asserts you would see the audience’s brain waves aligning with the presenter’s brain wave. He demonstrated the effect by placing participants in an MRI to watch an episode of Sherlock Holmes that they had never seen before. He measured their brain waves and asked them to retell the story they had just watched –and the brain waves were identical. Then he played the recounting of the story to a second set of participants who had also not seen the episode. Their brain waves aligned with the same pattern as the first participants, demonstrating the coupling in the diagram below.

Presentations expert, David JP Phillips, puts all the above together – prompting the emotions created by storytelling and demonstrating why storytelling is the most effective form of storytelling in this TED talk:

Storytelling in science communication can be challenging. Scientists are trained to be objective and mostly work with inanimate objects and facts. They are also rarely taught to communicate with public audiences. A small percentage of scientists are good communicators, and some make it their profession, like Neil deGrasse Tyson and Brian Cox. But for most scientists, recounting their personal journey is rarely shared – how the discovery was made, and that interests us the most.

References:

Cormick, C. (2019). The Science of Communicating Science, CSIRO Press.

Phillips, D.J.P. (2013). TED Talk, Stockholm.